Shoreline

In 1914, the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians sued Chicago for land along the lakefront. As co-signers of the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, they had given up their land in Illinois up to the shore of Lake Michigan. Since then, the city had created land beyond the shore, including valuable property such as Streeterville. The Potawatomi argued for return of this unceded land or payment for its value. The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court, where, predictably, the Potawatomi lost.

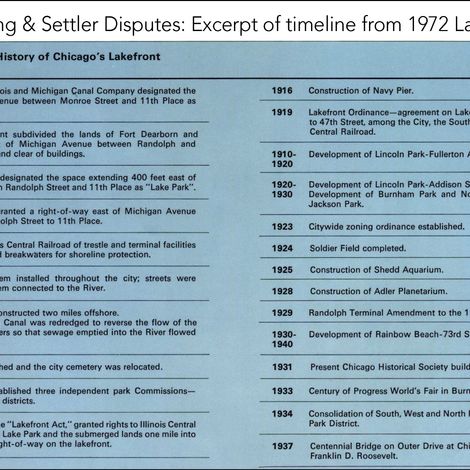

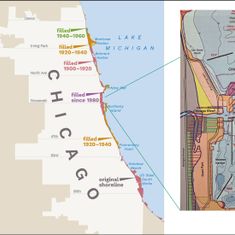

My research on this case has taken me down fascinating paths about the engineering of the lakefront and competing interests in this piece of land. The landfill now consists of more than 5.5 square miles, made of rubble from the Chicago Fire, dirt from highway construction, sand from the Indiana Dunes, slag from US Steel, and trash. Most of this land is now parks and Lake Shore Drive, inspired by Daniel Burnham’s 1909 Plan of Chicago. This plan is often described as visionary and enlightened, but it was financed by the Commercial Club in order to promote business and reduce labor conflict, viewing parks as recreational outlets for working class anger. Even then, different factions of the city’s elites fought every strip of landfill to make Lake Shore Drive.

Today, the city is proud of its lakefront as a great civic asset, but as the Potawatomi insisted, this land is Native land. What does it mean that this much-vaunted lakefront was born from an elitist vision of urban control and breaks treaty law by its existence?

Based on this research, I am working on “Shoreline,” an audio walk along the lakefront. Audio recordings on the Gesso.fm app will be triggered by GPS location at different points along the 30 miles of shore from Evanston to the Indiana border. Through readings of treaties, laws, poems, stories, and songs in English, Potawatomi and Korean, the audio walk will invite participants to contemplate the complex histories and meanings of Chicago’s lakefront.